This is an excerpt from a longer guide I’m developing that takes teachers through the process of rewriting learning outcomes, assessments, and activities to support diversity and inclusion in social studies and humanities courses. If you’d like to be alerted when the full guide is ready, please e-mail me: madsenbrooks -at- gmail -dot- com.

Finding content in support of diversity and inclusion

Assuming you have some sense of which knowledge or skills you’d like to assess, what content should you be teaching to help students develop that knowledge or those skills? You may be unfamiliar with any but the most obvious (Martin Luther King Jr.) or traditional (Harriet Tubman, Susan B. Anthony) of what’s available. Or maybe you’ve already undertaken some preliminary research on a couple of potential topics, you’ve seen the vast extent of what’s available, and you’re overwhelmed.

Oh, and you have an extremely limited budget. But I don’t need to mention that part, do I? 🙂

Where do you start?

Remember the foundation you have laid

Obviously, you need to approach content acquisition and development with your learning outcomes, as well as how you’re going to assess students’ progress toward these outcomes, close at hand.

With those outcomes and assessments firmly in mind, one place to begin is grade level and discipline, with your state’s content standards. As you know, depending on your state’s politics and educational leadership, the standards may be more or less developed and specific. However, even states that occupy similar places on the political spectrum can differ in their approach. When it comes to World War II, for example, Idaho’s standards ask high school students only to examine how the U.S. emerged as a world leader during and following the war. Indiana’s standards, on the other hand, are much more detailed. While developing an understanding of World War II, for instance, Indiana students will “explain how the United States dealt with individual rights and national security during World War II by examining the following groups: Japanese Americans, African Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, and women” (USH.5.6).

You also will need to determine what kinds of content you seek: primary sources, secondary sources (e.g., books, articles, documentaries), lesson plans, worksheets, etc. Some of us, when embarking on the backward design process, have the time and inclination to develop everything ourselves, but there’s plenty of great curriculum already out there that you can adapt or use as-is—if you know where to look.

Finally, as you begin keyword searches and start browsing sites, you’ll want to know the specific subject matter. For the purposes of this exercise, let’s use the same learning outcome from Indiana’s content standards.

So, to review:

- Learning outcome: Explain how the United States dealt with individual rights and national security during World War II by examining the following groups: Japanese Americans, African Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, and women (USH.5.6).

- Grade level: high school

- Discipline: social studies/U.S. history

- Summative assessments:

- In small groups, students will draw on primary sources to make a digital story that captures midcentury Americans’ fears and concerns about national security.

- Students will write essays, illustrated with primary source images, making an argument about the impact of American intervention in World War II on the rights and freedoms of one of the groups named in the learning outcome.

- Formative assessments may include:

- Students will create, share, and further develop concept maps about the World War II-era experiences of each of the groups mentioned in the learning outcome.

- Throughout the unit, students will maintain an annotated scrapbook of primary and secondary sources related to the learning outcome. (Their concept maps will become part of this scrapbook.)

- Students will keep dialogic journals in response to Farewell to Manzanar.

- Prior to writing their individual essays, students will participate in a class-wide debate on whether it was appropriate for the U.S. government to restrict individual rights in the name of national security.

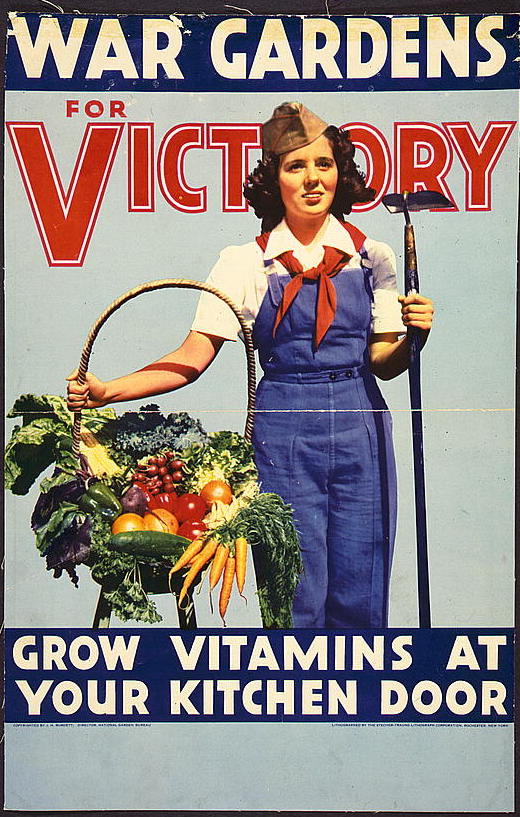

- Drawing on the aesthetic of WWII-propaganda-style posters, students will create posters with slogans touching on civil rights during our current “war on terror.”

- Subject matter: Japanese Americans’, African Americans’, Native Americans’, Hispanics’ and women’s experiences during World War II; balancing individual rights with national security

Once you have these six categories of information, you can begin to find content.

One important note before we go further: As you seek content, it’s important to remember not to be merely additive—that is, you shouldn’t include African-American history just during Black History month, or during units on slavery or the twentieth-century civil rights movement. Rather, even though it may be the primary focus during certain units, the history of African Americans—as well as that of other groups—should be integrated into the curriculum throughout the year. Keep this in mind as you search for content for all units in your course.

Digital repositories of social studies content

We’ll get to keyword searches later in this section of the guide, but first I want to share with you a few gold mines of primary sources, interpretations of the past (secondary sources), lesson plans, and other educational resources relevant to U.S. history. These organizations and institutions provide public access to a wealth of primary-source texts, historical photos, newspapers and magazines, archival film, and photos documenting art and artifacts.

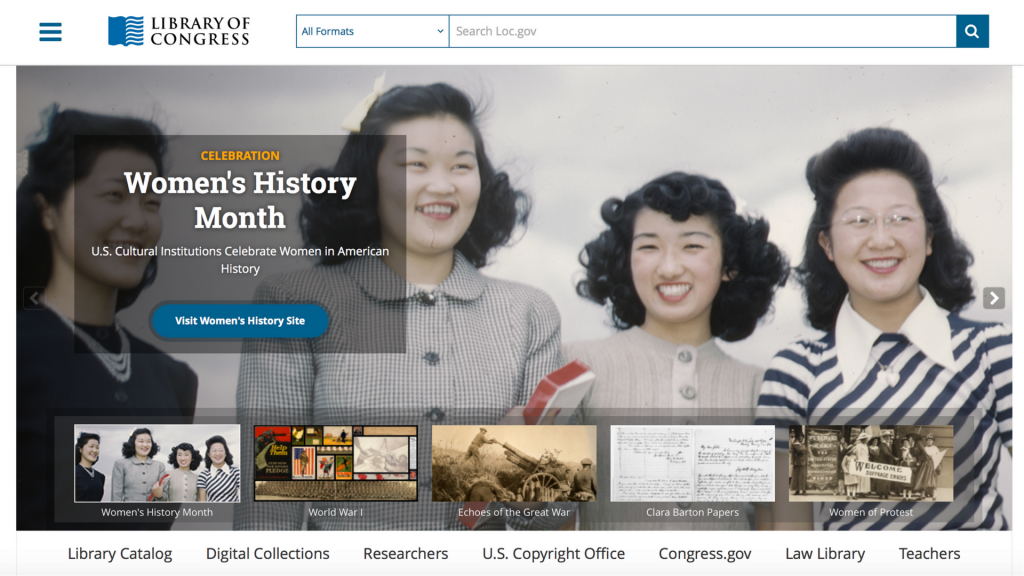

The Library of Congress

The Library of Congress is the research library of the U.S. Congress, as well as one of the three major repositories of the cultural and political history of the United States (the others are the National Archives and the Smithsonian Institution). It is the largest library in the world. While only a small percentage of the Library of Congress’s holdings are online, you’ll find it is a rich source of texts, images, and video clips representing all eras of U.S. history.

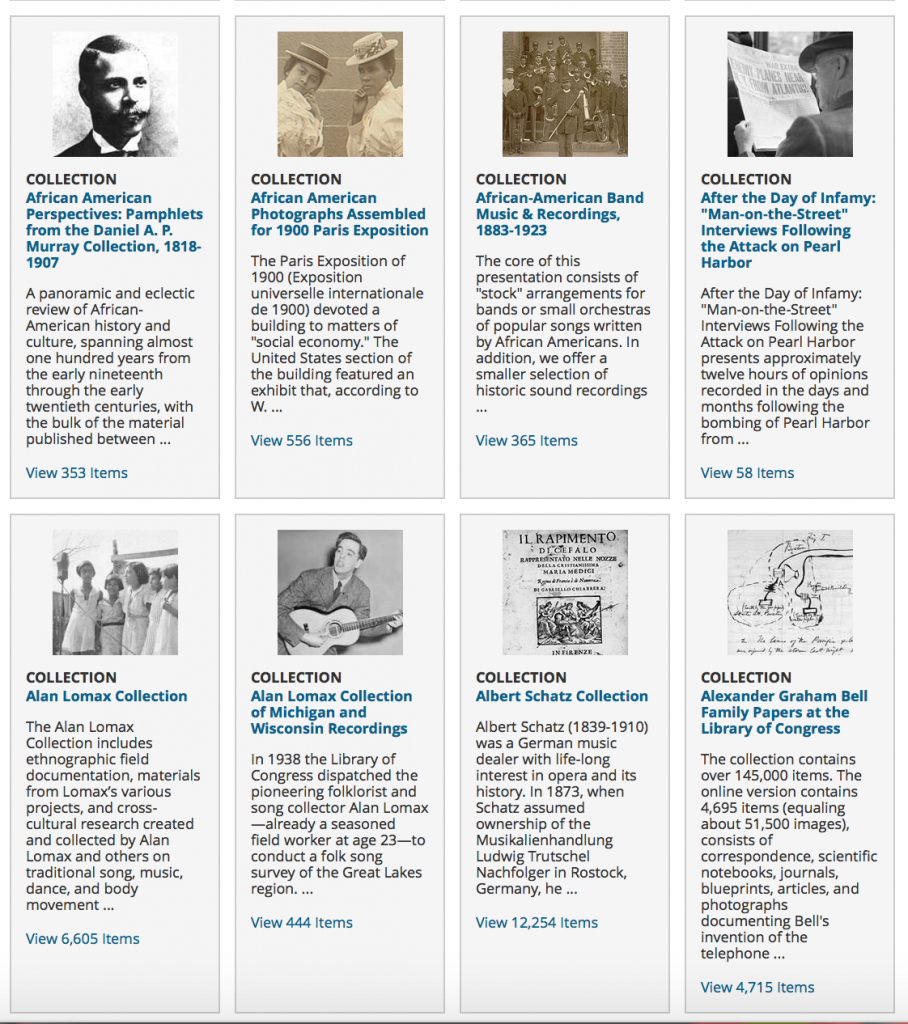

You can search the site’s digital artifacts simply by entering keywords into the search bar at the upper right of the home page. If you’d prefer to browse for information, you can do that, too. But be careful—I find spending hours on the site, mining it for curricular riches and exploring out of pure intellectual curiosity. When I clicked “Digital Collections” on the menu under the big photo on the home page, I saw a ton of collections I could use to develop amazing units around women’s history, African-American history, technology, and music history:

You can search the site’s digital artifacts simply by entering keywords into the search bar at the upper right of the home page. If you’d prefer to browse for information, you can do that, too. But be careful—I find spending hours on the site, mining it for curricular riches and exploring out of pure intellectual curiosity. When I clicked “Digital Collections” on the menu under the big photo on the home page, I saw a ton of collections I could use to develop amazing units around women’s history, African-American history, technology, and music history:

The Library also maintains an extensive collection of resources for teachers, including classroom materials and professional development resources. You can search the classroom materials by standards (Common Core, state content, or organization). You can learn as well how to use primary sources in your lessons, and access free, interactive ebooks to use in your class. There are also several dozen lesson plans available, such as these on Indian boarding schools; Japanese American internment; women in the Civil War; immigration and migration; and race relations, baseball, and Jackie Robinson.

Of particular note for our learning outcome regarding the experiences of specific groups in World War II, searching the Library of Congress’s website turns up these resources:

- “Japanese American Internment: Fear Itself” (lesson plan)

- “Women Come to the Front”—women journalists and photographers in World War II (short bios, essays, and photos)

- “Ansel Adams’s Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar” (photos, articles, and essays – compare with Dorothea Lange’s photos of the Japanese internment available through Calisphere)

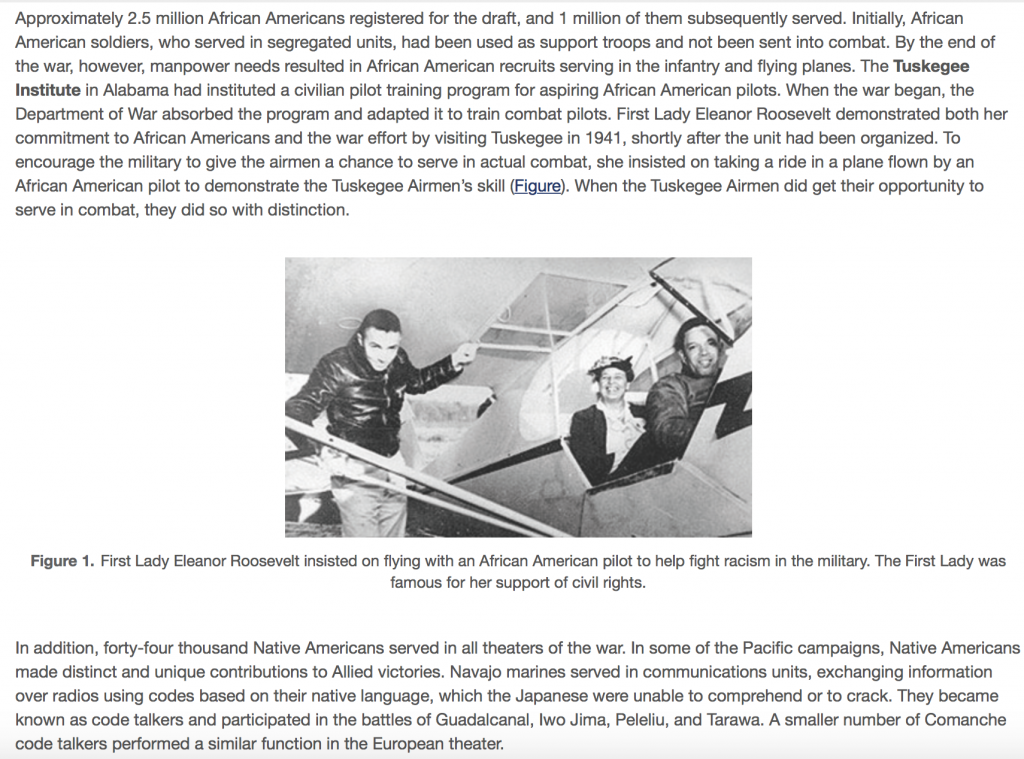

- Photos of the Tuskegee Airmen (photos by Toni Frissell)

- “Women at War” (digital resource, including video and audio interviews of veterans, as well as photos)

- Storycorps stories related to World War II (audio interviews, including this one with a Japanese American on the days preceding internment and this one with the spouse of a training officer for the Tuskegee airmen)

- Zoot Suit Riots (photos)

- and more—do some keyword searches or browse the digital collections.

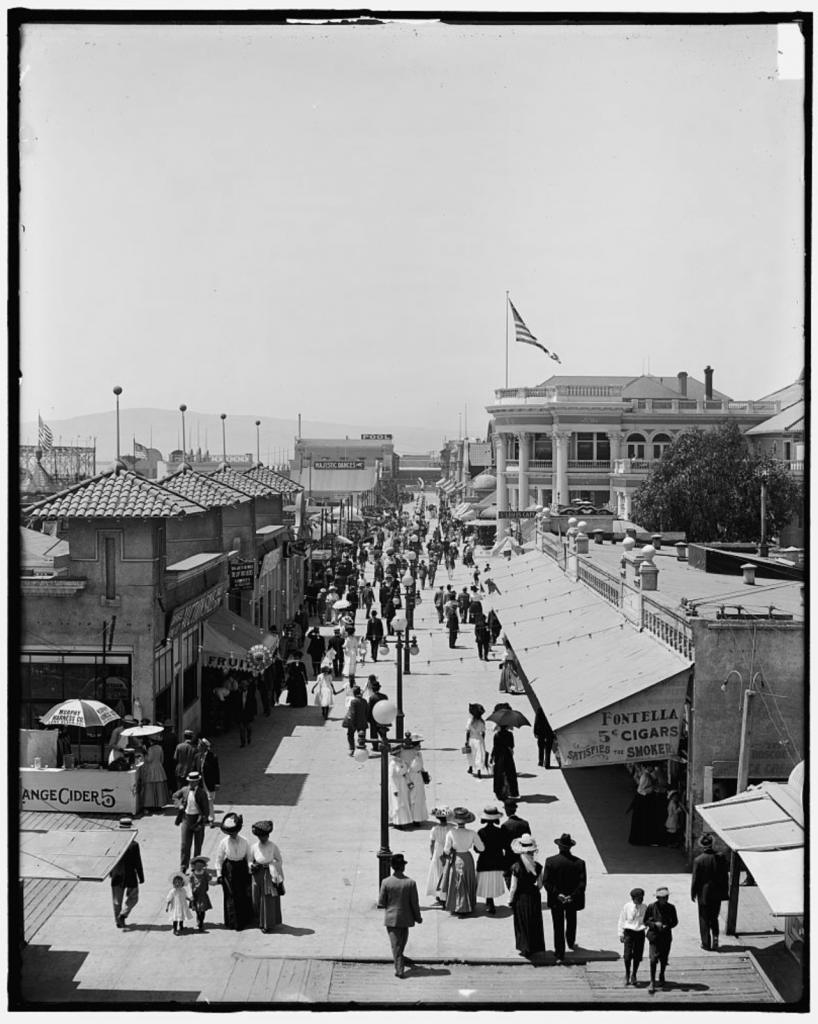

Of course, keyword searches also may prove very fruitful. I like to use them when I’m looking for more local or regional historical texts or images that may not be included in organized digital collections. Here, for example, is one photo I found when searching for images from my hometown of Long Beach, California. High school and college students in particular might find it interesting to approach history through photographic analysis of such prints (and of course The Library of Congress offers guides for analyzing primary sources, including photographs):

And look! You can also learn about grants available for “school districts, universities, cultural institutions, library systems and other educational organizations” that wish to teach with primary sources.

The Smithsonian Institution

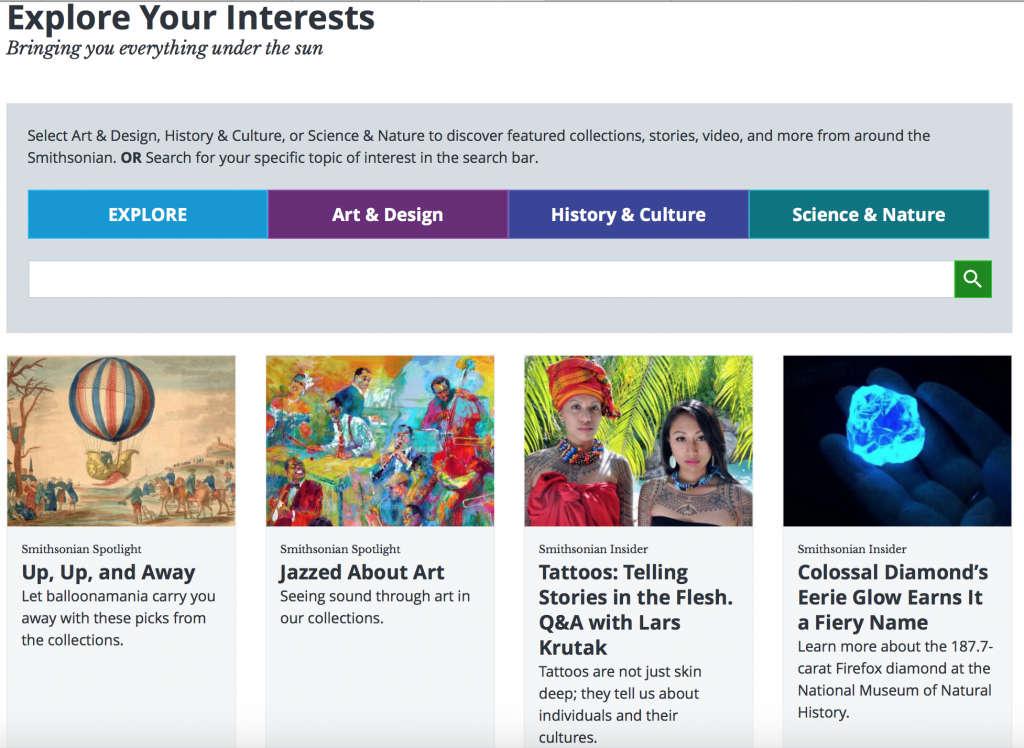

The Smithsonian comprises 19 museums, the National Zoo, several research and cultural centers, and additional educational programs. Many museums and programs have their own resources for educators and for kids. You can also explore by interest, entering search terms or browsing by topic:

A search for our topic, World War II, pulls up more resources that we can reasonably explore:

I recommend, then, that you start with “Exhibitions” or “Articles,” which provide more organized and curated topics:

- “Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II” (online exhibit)

- “The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps, 1942-1946” (images of art by interned Japanese Americans)

- “Muslim American Kids Read Letters by WWII Japanese Americans” (video)

- “Double Victory: The African American Military Experience” (information about a physical exhibition at the National Museum of African American History and Culture; you might use some of the terms used here to search the Smithsonian’s digital collections in the “Explore Your Interests” section above.)

- “Creating the Cadet Nurse Corps for World War II” (article with images)

- “See World War II through the Lens of an African American Soldier” (article with images)

- “Comic book project helps teens discover and share stories of Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II” (article with images, plus printable comic books)

- Japanese American Incarceration Era Collection (very short articles introducing curated collections of objects from incarceration, plus interviews)

- “‘Honor Et Fidelitas’: The awarding of a Congressional Gold Medal to the ‘Borinqueneers’” (article with images; the article offers great keywords for further searches)

- “Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1942-1964 / Cosecha Amarga Cosecha Dulce: El programa Bracero 1942-1964” (very short articles introducing curated collections of images)

- “The Power of Words: Native Languages as Weapons of War” (video)

- and more—click around the individual images to unearth relevant photos, art, and artifacts

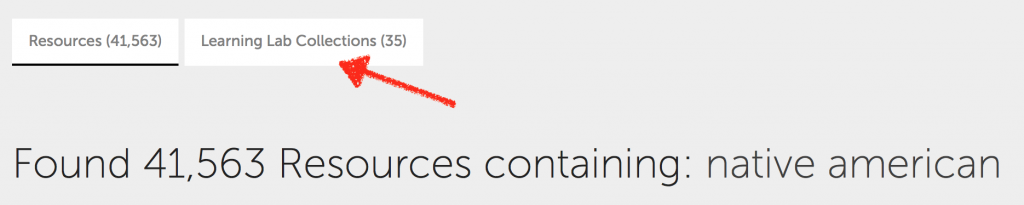

One of the Smithsonian’s flagship digital programs is the Smithsonian Learning Lab, which allows users to explore the Smithsonian’s digital collections, create personal collections and resources, and share what they discover. The resources in the Learning Lab are extensive, but not always well-organized as raw search results; see, for example, this search for “Native American,” which for me resulted in 41,563 resources. Note, however, that if you click on the tab labeled “Learning Lab Collections,” you’ll find several organized collections.

Each collection contains multimedia resources. For example, one of the collections resulting from this search, Native American Beading, contains examples of Native beading, a link to a relevant website, an interview with an artist, a demonstration video, and printable instructions on how to make a beaded daisy chain bracelet.

The National Archives

The National Archives keeps the nation’s records. As the National Archives’ website explains, “Of all documents and materials created in the course of business conducted by the United States Federal government, only 1%-3% are so important for legal or historical reasons that they are kept by us forever. Those valuable records are preserved and are available to you, whether you want to see if they contain clues about your family’s history, need to prove a veteran’s military service, or are researching an historical topic that interests you.”

The National Archives doesn’t have as robust an education portal as do the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress, in part because many of its links to teaching activities are broken. Still, I encourage you to browse its educator resources, which include special topics and tools to use with students, professional development opportunities, distance learning programs, and National History Day resources.

Here are some National Archives resources relevant to our learning outcome about diverse experiences during World War II:

- “Japanese American Internment” (multimedia resources assembled for the 75th anniversary of internment)

- “Japanese Relocation During World War II” (essay and primary source documents)

- “Memorandum Regarding the Enlistment of Navajo Indians” (essay and primary source document)

- “Pictures of African Americans During World War II” (photos)

- “Women” (links to resources hosted on the National Archives website or elsewhere about women’s history, including many collections related to women during World War II)

- “Mexican American Soldiers Mistreated” (short article and primary source document)

- “Zoot Suit Riots” (short article and several primary source documents)

- and more

The Digital Public Library of America

The Digital Public Library of America, or DPLA, is a portal that provides public access to digitized cultural heritage resources, a platform that enables new and transformative uses of this digitized heritage, and an advocate for an open intellectual landscape. Through DPLA, users can search by keyword, browse online exhibitions, browse regional resources via a U.S. map, explore resources by year using a timeline, and download apps that allow users to interact with the digitized resources of DPLA. DPLA also provides dozens of primary source sets with accompanying teaching guides, as well as resources for students and teachers participating in National History Day.

Relevant to our learning outcome:

- “Japanese American Internment during World War II” (a primary source set and teaching guide)

- “World War II: Women on the Home Front” (a primary source set and teaching guide)

- “Mexican Labor and World War II: The Bracero Program” (a primary source set and teaching guide)

- “Attacks on American Soil: Pearl Harbor and September 11” (a primary source set and teaching guide)

- and more

Calisphere

Many states and state universities have large digitized collections related to their regions’ history and culture. (The Library of Congress maintains a long but by no means complete list of such repositories.) Because California was a particularly diverse state from its founding, however, California’s archives are especially rich sources for multicultural education. Calisphere itself explains it serves as “your gateway to California’s remarkable digital collections. Calisphere provides free access to unique and historically important artifacts for research, teaching, and curious exploration. Discover over 750,000 photographs, documents, letters, artwork, diaries, oral histories, films, advertisements, musical recordings, and more. The collections on Calisphere have been digitized and contributed by all ten campuses of the University of California and other important libraries, archives, and museums throughout the state.”

- “The 442nd Regimental Combat Team” (overview and images related to a Japanese-American unit during World War II)

- “Women in the Workforce” (overview and images related to American women’s employment during World War II)

- “Life on the Homefront” (overview and images of life in the U.S. during World War II)

- “The Bracero Program” (overview and images of the migrant labor program, which began in 1942—see also the Bracero History Archive)

- “Richmond [Calif] Shipyards” (overview and images of a diverse labor force building ships during World War II)

- “San Joaquin Valley Japanese Americans in WWII” (images and texts, including bulletins published at relocation centers)

- Zoot Suit Riots (primarily images)

- Japanese American Relocation Digital Archive (JARDA) (“thousands of primary sources documenting Japanese American internment, including personal diaries, letters, photographs, and drawings; US War Relocation Authority materials, including camp newsletters, final reports, photographs, and other documents relating to the day-to-day administration of the camps;and personal histories documenting the lives of the people who lived in the camps, as well as of the administrators who created and worked there.”)

- and more

The Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is “a non-profit library of millions of free books, movies, software, music, websites, and more.” It’s a wild and woolly collection of resources of all kinds uploaded by enthusiasts of open source, public domain, and Creative Commons-licensed materials. This is not usually my go-to resource unless I’m looking for a digitized version of a book published before 1923 (such books are in the public domain in the U.S.) or that may have otherwise fallen out of copyright. Sometimes I’ll find exactly the primary source materials I’m looking for, and often I’ll find a secondary source I can mine for ideas, inspiration, and additional reference sources for my lessons. Take, for example, this paper that, among other things, considers the pachuchos of the 1940s, including the Zoot Suit Riots and the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial, or this oral history of a woman who left Iowa to work in the Richmond, California shipyards during World War II.

Via the Wayback Machine, the Internet Archive also provides a way to view web pages as they looked in months or years past, including websites that have disappeared altogether. I use the Wayback Machine all the time to find educational resources I have used in previous semesters but that have since vanished; all I have to do is paste the now-broken URL into the search bar.

Open Educational Resources (OER)

I’m a huge proponent of open educational resources (OER) in K-20 education. If you’re not familiar with OER, you can download a brief overview of OER and how it works, but in short open educational resources are free of cost, flexible, and often kept up to date in ways that print materials aren’t.

OER offers K-12 schools and college students who can’t afford expensive textbooks a way to ensure students get access to the materials they need to learn. Not surprisingly, using OER can boost both retention and graduation rates. Openly licensed resources are, therefore, one of the pillars of multicultural education.

If you’re looking for textbook-like resources to use with your students, I strongly encourage you to check out OER textbooks and other openly licensed educational resources. (Did you notice that everything to which I’ve linked above is free of cost and much of it is openly licensed?) All OER textbooks are free to use, often are up-to-date with diverse representations of life in the U.S., and many of these textbooks are licensed in ways that allow you to excerpt, revise, and remix their content. You can tailor the content for your specific group of students!

Here, for example, is a section of the OpenStax textbook U.S. History about the home front during World War II. It provides an overview of many topics relevant to our sample learning outcome, including the experiences of women and people of color, and it prompts the students to consider primary sources. Just because OER is free to use doesn’t mean it’s of poor quality—indeed, quite the opposite is often true. Check it out:

Humboldt State University maintains one compendium of OER texts across disciplines, including U.S. history, but a little searching will turn up countless OER texts, videos, images, and other learning resources. Unfortunately, there isn’t a single aggregator of OER, so I recommend searching several sites dedicated to making these resources easier to find, including the OER Commons, the Open Textbook Library, and Textbook Revolution. You also can find some great resources using the Creative Commons search tool.

Specialized archives and databases

Densho documents Japanese American life from the early 1900s through the 1980s, “with a strong focus on the World War II mass incarceration.” It offers a core story about internment, extensive primary source archives, an encyclopedia about “the history of the Japanese American WWII exclusion and incarceration experience,” and teaching and learning resources for teachers and students. It’s one of the absolute best sources on the internment, both in terms of its depth and breadth of primary sources and its packaging of those sources into educational materials.

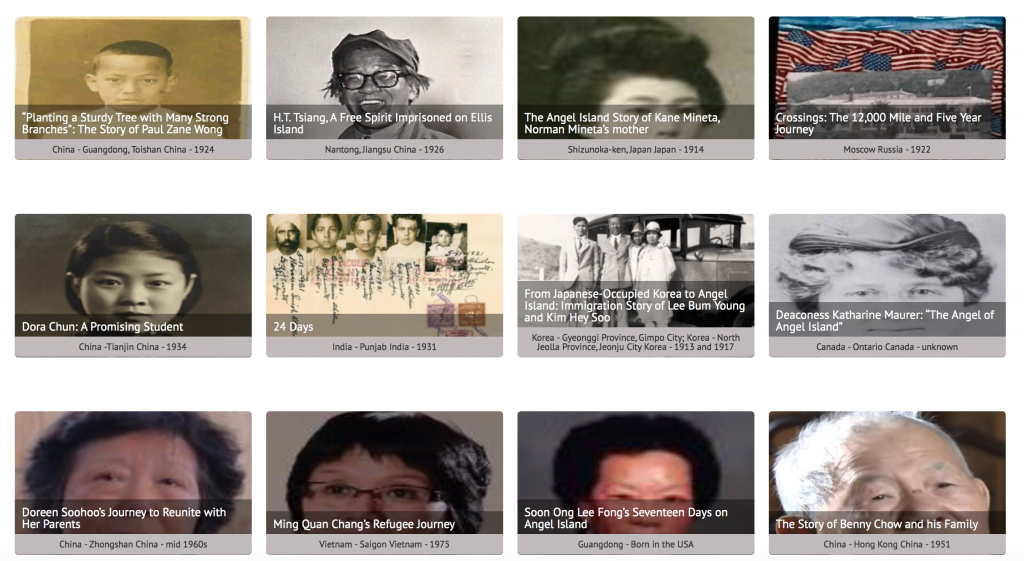

The Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF) shares the history of immigration to the west coast of the United States, delving into the lives of immigrants from all over the world, but with a special focus on immigrants from Asia. Its website offers a history of the Angel Island immigration station, which served as a processing station for mostly non-European immigrants to California and the wider west coast. It also served as a detention station. The AIISF recommends a number of educational resources, but the highlight of the site may be its Immigrant Voices project, an ever-growing “archive of personal stories of immigrants to the Pacific Coast, from Angel Island Immigration Station detainees to those arriving today.” Immigrant Voices is an excellent resource for teaching about immigration to the United States. Students also are welcome to use primary sources and interviews with immigrants to the West Coast to craft their own stories and submit them to AIISF for inclusion in Immigrant Voices.

One emerging area of archival focus is LGBT history. There are several places online where students can browse for content related to the history and culture of LGBT individuals and communities. Among these are:

- LGBT Community Center National History Archive: Preserves a rich history and heritage heritage. The archive documents the experiences of LGBT people throughout the years. Sources include photography, letters, news clipping, audio recordings, broadcasts, and journals.

- The GLBT History Society offers several online exhibitions, including Outranks: GLBT Military Services from World War II to the Iraq War.

- The Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies at the University of Minnesota has extensive digitized collections related to diverse LGBT topics, including Two Spirit people among Native Americans. The collection’s website describes its physical collections, but allows users to search for digitized materials from its home page.

- ONE Archives Foundation offers traveling exhibitions comprising large panels of text and images that you can bring to local schools, museums, and community organizations. ONE also provides a list of educational resources where you can learn more about LGBT experiences.

- Unerased provides specialized professional development and academic content for K-12 teachers. It also has created videos featuring LGBT stories and voices.

- Finally, don’t discount the holdings of your local libraries—especially college and university libraries. Call their reference desk or special collections librarians and ask what resources are available. My own local university library, for example, has assembled and digitized a No On One collection that documents “the events surrounding Proposition One (1992-1994), an anti-homosexual special rights referendum that appeared on the Idaho general election ballot in November 1994.”

If you’re interested in finding journalistic coverage of particular historical events, checking out the news for certain dates, or delving into the past of a particular state, then you should check out Chronicling America, a joint project of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress. This is an excellent site if you want your students to explore how historical events were reported in the U.S. prior to 1924—so it’s not going to help much with our sample learning outcome, but it’s a rich resource for earlier centuries. (Why 1924? Under U.S. copyright law, articles published prior that year have fallen into the public domain and can be shared without limitation.) If you can’t find what you need in the digital archive, you can use the site’s U.S. Newspaper Directory, a catalog of more than 150,000 newspapers published in the U.S. since 1690 that can help you identify what titles exist for a specific place and time, as well as how to access them.

#Syllabus projects

In recent years, in response to various cultural phenomena and events, academics and others have compiled several resource lists designed to help people better understand what’s going on, but especially from the perspective of underrepresented groups. These syllabi were widely shared on social media, each under its own hashtag—e.g., #FergusonSyllabus or #OrlandoSyllabus. These hashtag syllabi, as I’ve come call them, provide rich resources and insights on not only the events themselves, but also the historical and cultural contexts that brought them into being. Here are some of them:

- #FergusonSyllabus, on the 2012 shooting of Trayvon Martin

- #BlackLivesMatter Syllabus, on the movement that grew out of the protests in Ferguson

- #NativeLivesMatter Syllabus, in solidarity with Native Americans

- #StandingRockSyllabus, on the 2016-17 protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline

- #CharlestonSyllabus, on the 2015 shooting in Mother Emanuel church (It’s also an excellent book of readings)

- #OrlandoSyllabus, on the 1016 Pulse nightclub shooting. It has several versions: from the Georgia State University library, from Bully Bloggers, from the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, and an extensive crowdsourced version.

- #LemonadeSyllabus, on Beyoncé’s 2016 album

- #BaltimoreSyllabus, on the 2015 death of Freddie Gray

- Trump 101 Syllabus, on the campaign and popularity of Donald Trump

- Trump Syllabus 2.0, which emphasizes sources on “the racism, sexism, and xenophobia on which Trump has built his candidacy”

- Rape Culture Syllabus, in response to a video of Trump joking about assaulting women

Flickr Commons

The photo-sharing site Flickr has a special section, The Commons, set aside for museums, libraries, and archives to share resources with no known copyright restrictions. Institutions from around the world have shared items from their vast collections. You can search the entire Commons, or you can browse by participating institution. Contributing institutions have organized their collections into albums. One of my favorites is this album from the Smithsonian of women in science; it contains more than 400 photos. If you browse within the Smithsonian’s collections, you’ll find plenty of inspiration for students writing diverse biographical sketches. Check out this image of Sophie Lutterlough, for example, and the accompanying caption provided by the Smithsonian on The Commons:

And there’s more. . .

As you know, the World Wide Web is an ever-expanding repository of all kinds of digital resources, and there’s no way one person can keep atop all the great content online. While I’ve tried to save you some searching by highlighting key resources related to diversity in U.S. history and culture, you’ll turn up even more resources if you do your own investigating.